Last summer, concerns over the Democratic Party’s central voter information database, NGP VAN, prompted an intervention from top party officials to avert potential collapse before the November election. If the system failed, canvassers would revert to manual methods, hindering their outreach efforts. Amid warnings from the database’s private owners about data management issues, Democratic engineers worked to stabilize the system. Significant unease about the database’s reliability has fueled discussions about overhauling or replacing it. Party leaders are now contemplating activating a contract clause for source code access, highlighting their dependency on a for-profit company amid worries over cuts and layoffs.

Concerns surrounding a vast database of voter information, deemed the backbone of the Democratic Party, escalated significantly last summer. In response, leading Democrats organized an unprecedented intervention to ensure its operation remained stable through the November election, as reported by various insiders.

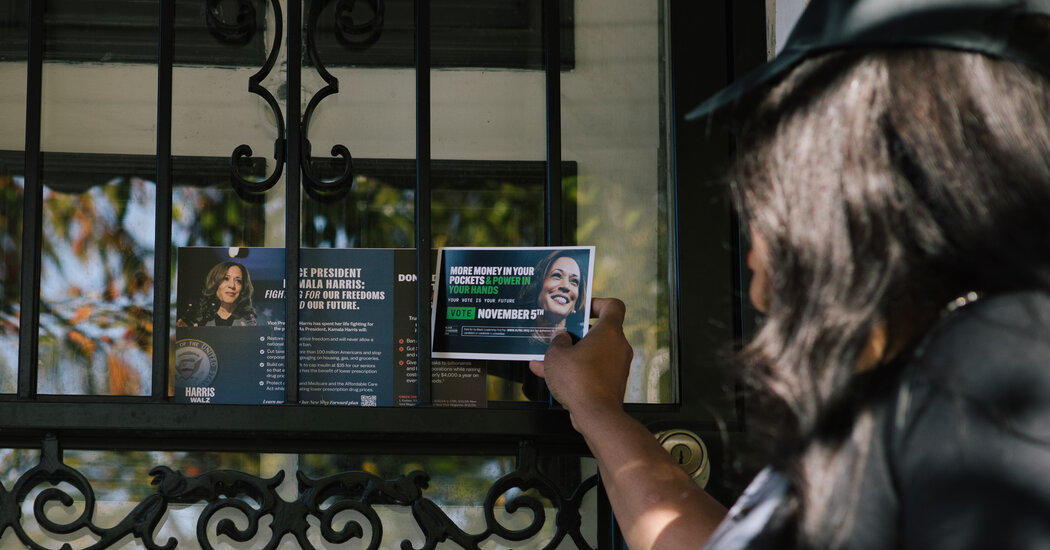

If it had failed, the party’s comprehensive get-out-the-vote strategy could have faced severe setbacks, compelling canvassers to revert to pen-and-paper methods instead of utilizing smartphones, and leaving campaigns largely uninformed about which doors to approach or which numbers to dial.

To avert such a disaster, a select group of engineers from the Democratic National Committee alongside the Kamala Harris campaign dedicated months to ensuring the database’s functionality, according to sources.

The privately-owned company managing the database alerted several Democratic organizations that it was struggling to cope with the heavy volume of data being transferred. Meanwhile, an external organization rushed to implement a workaround, while affluent Democratic donor Allen Blue was called upon to finance an urgent engineering initiative to maintain data flow.

“This cannot happen again,” stated Mr. Blue, a LinkedIn co-founder, emphasizing that revamping the party’s technological framework must be integral to any broader Democratic revitalization efforts. “Technology and data form the backbone of modern campaign strategies.”

This situation, previously unreported, has intensified worries among the party’s leadership regarding their heavy reliance on a for-profit entity, whose majority owner is a private equity firm that has enforced layoffs in recent years to cut expenses.

The company asserts that the database was functioning properly.

This week, during a gathering of Democratic technology strategists in Puerto Rico to deliberate on the future of data and technology for the party, the fate of the NGP VAN database system was a key topic.

On Wednesday, the Movement Cooperative — a nonprofit providing data and technology assistance to progressive organizations — sought proposals for developing a new voter data system as a potential replacement for NGP VAN.

Michael Fisher, who joined the Harris campaign last summer to assure the dependability of its technology, remarked that the database had been struggling for years, requiring significant and distracting effort merely to function effectively in 2024.

“This conversation should not recur in another four years,” Mr. Fisher urged, advocating for the establishment of a new database. “The only reason I’m speaking to you now is that this is the moment for change.”

Currently, the Democratic National Committee is contemplating just that. Officials are exploring a drastic option — invoking a hidden clause in the party’s contract with the database owner to request a copy of the source code, according to two individuals familiar with the discussions who asked to remain anonymous.

The committee chose not to answer questions regarding its plans.

“The technology infrastructure of the Democrats ensures that we are prepared to win elections across the board, both now and in the future, with important safeguards and redundancies to safeguard our data and guarantee that Democrats are never caught off guard,” stated Arthur Thompson, chief technology officer for the D.N.C., highlighting it as a priority for the party’s new chair, Ken Martin. “We will be reviewing every vendor relationship to ensure they are fully equipped for the current demands.”

Mr. Thompson was among the party’s technology strategists present in Puerto Rico.

Chelsea Peterson Thompson, the general manager of NGP VAN (unrelated to Mr. Thompson), countered claims that the product was failing, asserting that it is “the gold standard for political organizing tools.”

She implied there could be ulterior motives behind the criticism.

“It is neither surprising nor new that detractors want the narrative to be the opposite, as it serves their personal or commercial interests,” Ms. Thompson stated, adding, “The platform facilitated the largest voter outreach initiative in human history without stability or downtime issues.”

She also denied any near-failure of the platform, asserting it was “not close at all,” and characterized the final weeks leading to the election as “remarkably calm.”

Founded in the late 1990s, NGP VAN resulted from the 2010 merger of a political fundraising specialist, NGP Software, and the Voter Activation Network, which was focused on voter outreach.

Commonly referred to as VAN among Democrats, it houses billions of records, representing virtually all information the party has collected on tens of millions of Americans. Nearly every Democratic-aligned campaign or organization can access these records to leverage the information for persuasion, organization, or mobilization efforts.

As the saying goes among party operatives: “If it isn’t in VAN, it doesn’t exist.”

In 2021, NGP VAN was acquired as part of a $2 billion deal by the private equity firm Apax Partners, which established a subsidiary named Bonterra that now oversees the company.

(The Republican Party also depends on a for-profit firm, Data Trust, to manage its voter files. However, Data Trust has largely remained under the supervision of party-aligned operatives since its inception nearly 15 years ago.)

Democratic officials have expressed concerns, both publicly and privately, about the adverse effects of cost-cutting, layoffs, and underinvestment since the acquisition. An internal DNC memo from early 2023, obtained by The New York Times, indicated that VAN’s infrastructure was already “inflexible, slow, and unreliable, especially during peak usage periods.”

“It is probable that Bonterra will persist in trimming costs and reallocating development resources away from the core tools employed by Democratic campaigns,” the memo warned.

By early 2024, the concerns had escalated to the point that the D.N.C. contemplated invoking the source-code clause, which would effectively permit them to transfer their data elsewhere. The committee drafted a letter from its executive director, Sam Cornale, addressed to Bonterra’s CEO, citing worries about the database’s stability and the support it was receiving from the company. The draft expressed that the D.N.C. required the code to “safeguard the Democratic Party’s interests amid potential risks during this uncertain period.”

The letter was never dispatched. Party officials, alongside Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s re-election campaign — which lacked its own chief technology officer — concluded that such an extreme step could be detrimental in the midst of an election year.

They opted to continue with NGP VAN, despite their concerns.

Nevertheless, a segment of Democrats worried about the system’s reliability — following some difficulties during the 2020 Biden campaign — devised a backup strategy through an organization called the Movement Infrastructure Group. This effectively established an alternate route for transferring substantial volumes of data in and out of the NGP VAN system.

Anxiety over a potential collapse of the NGP VAN system intensified last summer after Ms. Harris secured the Democratic nomination for president, as the company alerted her campaign and the D.N.C. that its canvassing app could not accommodate the demand projected by the campaign, according to two knowledgeable individuals.

From that moment leading to the election, both the Harris campaign and the D.N.C. employed technical experts full time to support the functionality of NGP VAN’s tools, insiders reported.

Nevertheless, in October, Mike Pfohl, president of Empower Project, a progressive nonprofit involved in organizing work, expressed his surprise when NGP VAN requested that his organization reduce the data it was adding to and extracting from the database.

“We were informed that we were creating too much traffic for them and needed to scale back the amount of data sent to prevent overwhelming others,” Mr. Pfohl recounted.

Ms. Thompson, the NGP VAN general manager, clarified that only a limited number of software vendors — initially planning “thousands of requests per second” to the database — were impacted and that NGP VAN had collaborated with these groups to address their requirements.

Mr. Pfohl noted that his organization managed to adapt, but that such throttling could have been catastrophic for others. He expressed disdain for NGP VAN’s ownership by private equity, arguing that the pursuit of profit contradicted the database’s original purpose.

“The mission should take precedence,” he asserted. “The notion that we would be utilizing dues from union members to ultimately enhance someone’s yacht fund is infuriating to me.”