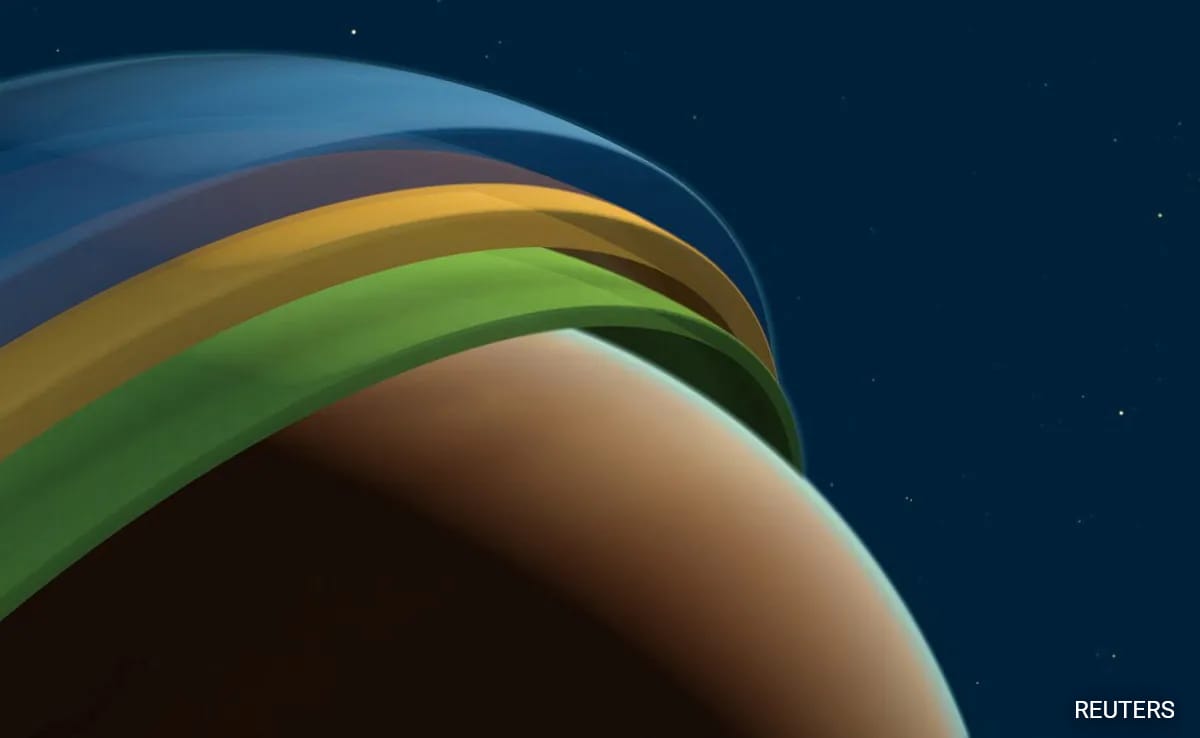

Astronomers have successfully mapped the three-dimensional structure of WASP-121b’s atmosphere, identifying three distinct layers akin to a wedding cake. This ultra-hot gas giant, orbiting a star hotter than our sun, features a unique stratification with iron, sodium, and hydrogen at different levels, alongside intense winds. The lower layer contains gaseous iron due to extreme heat, the middle layer exhibits a jet stream with winds over 43,500 mph, and the upper layer loses hydrogen into space. This groundbreaking observation challenges existing atmospheric models and could guide future studies of smaller, Earth-like exoplanets.

Washington:

Astronomers have, for the first time, successfully unraveled the three-dimensional design of the atmosphere surrounding a planet that lies outside our solar system. This discovery has unveiled three layers reminiscent of a wedding cake on an intensely hot gas giant that orbits closely around a star that is both larger and hotter than our sun.

The research team examined the atmosphere of WASP-121b, known also as Tylos, by utilizing all four telescope units of the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope located in Chile. They uncovered a distinct stratification of layers composed of varying chemical elements and violent winds.

Previously, researchers had been able to identify the atmospheric chemical makeup of certain exoplanets but lacked the capability to map their vertical structures and distribution of chemical elements.

WASP-121b is categorized as an “ultra-hot Jupiter,” a type of large gas planet that orbits very close to its star, resulting in extreme temperatures. Its atmosphere is primarily made up of hydrogen and helium, similar to that of Jupiter, which is the largest planet in our solar system. However, the atmospheric conditions on WASP-121b are unlike anything encountered before.

The scientists identified three distinct layers by searching for specific elements. The bottom layer was marked by the presence of iron, which exists in gaseous form due to the extreme heat in the atmosphere. Winds transport gas from the consistently hot side of the planet to its cooler side.

The middle layer was distinguished by the presence of sodium, featuring a jet stream that circulates around the planet at an astonishing 43,500 miles (70,000 km) per hour—stronger than any winds observed in our solar system. The upper layer was characterized as being primarily composed of hydrogen, with some of this layer escaping into space.

“This structure has never been documented before and contradicts existing predictions regarding atmospheric behavior,” stated astronomer Julia Victoria Seidel from the European Southern Observatory and the Lagrange Laboratory at the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur in France. She is the lead author of the study published this week in the journal Nature.

The researchers also discovered titanium in gaseous form within WASP-121b’s atmosphere. On Earth, neither iron nor titanium can be found in the atmosphere as they exist as solid metals due to our planet’s comparatively lower temperatures. However, Earth does possess a sodium layer in its upper atmosphere.

“The most thrilling aspect of this study is that it pushes the boundaries of what current telescopes and instruments can achieve,” remarked study co-author Bibiana Prinoth, a doctoral student in astronomy at Lund University in Sweden.

WASP-121b has a mass similar to that of Jupiter but boasts twice its diameter, making it fluffier. The planet is situated approximately 900 light-years away from Earth in the direction of the Puppis constellation. A light-year signifies the distance light travels in one year, which is 5.9 trillion miles (9.5 trillion km).

Being tidally locked, one side of WASP-121b perpetually faces its star while the opposite side remains in darkness, much like the moon’s relationship with Earth. The star-facing side experiences temperatures around 4,900 degrees Fahrenheit (2,700 degrees Celsius/3,000 degrees Kelvin), while the cooler side sits at about 2,200 degrees Fahrenheit (1,250 degrees Celsius/1,500 degrees Kelvin).

The planet orbits its star at roughly 2.5% the distance from Earth to the sun. It is located about a third closer to its star than Mercury, our solar system’s innermost planet is to the sun, resulting in a rapid orbital completion of just 1.3 days.

Its host star, named WASP-121, is approximately 1.5 times the mass and diameter of the sun and is also hotter.

Understanding the structure of an exoplanet’s atmosphere could prove beneficial as astronomers seek smaller rocky planets that may support life.

“In the coming years, we are likely to make similar observations regarding smaller and cooler planets that are more akin to Earth,” Prinoth noted, particularly with the European Southern Observatory’s Extremely Large Telescope expected to be completed in Chile by the end of the decade, which will become the world’s largest optical telescope.

“These detailed studies are vital for contextualizing our place in the universe,” Seidel stated. “Is Earth’s climate unique? Can we apply theories we derive from our single data point—Earth—to explain the diverse population of exoplanets?”

“Through our research, we have demonstrated that climates can behave in ways that differ vastly from our predictions. There exists a much greater diversity out there than we observe at home,” Seidel concluded.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is published from a syndicated feed.)