Alvin F. Poussaint, a prominent psychiatrist and advocate for Black mental health, died at 90 in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. He gained recognition in the 1960s for his work in the civil rights movement and later shaped discussions on Black culture through his research and books, addressing the effects of systemic racism while also promoting personal responsibility. Poussaint consulted on “The Cosby Show” and wrote influential works like “Lay My Burden Down” on mental health crises among African Americans. He faced criticism for suggesting that extreme racism could be classified as a mental health issue. Poussaint’s legacy reflects his dedication to addressing racial injustices and mental health challenges.

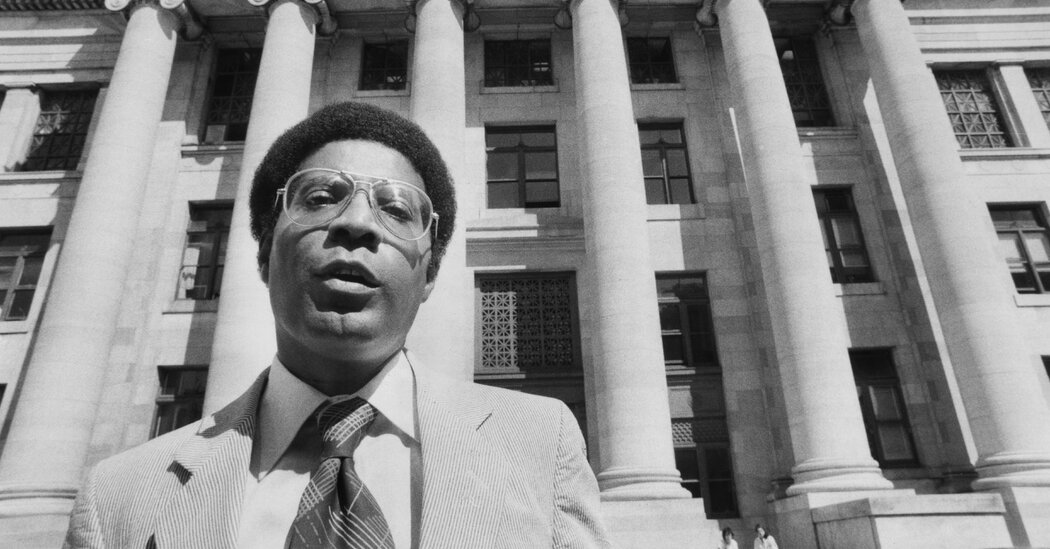

Alvin F. Poussaint, a psychiatrist who provided medical support to the civil rights movement in 1960s Mississippi, later emerged as a prominent figure in discussions surrounding Black culture and politics throughout the 1980s and ’90s, thanks to his research on the impact of racism on the mental health of Black individuals. He passed away on Monday at his residence in Chestnut Hill, Mass, at the age of 90.

His wife, Dr. Tina Young Poussaint, verified the news of his passing.

Dr. Poussaint devoted most of his career to teaching and serving as associate dean at Harvard Medical School, first gaining attention in the late 1970s when the enthusiasm of the civil rights movement was waning under the pressure of white backlash and doubt over Black advancement in a predominantly white society.

In his works, such as “Why Blacks Kill Blacks” (1972) and “Black Child Care” (1975), he navigated the contentious space between leftist perspectives that attributed the struggles of Black America to ongoing racism and right-leaning viewpoints asserting that it was the responsibility of Black individuals to shape their own destinies post-civil rights era.

Through thorough research and clear writing, Dr. Poussaint (pronounced pooh-SAHNT) acknowledged the ongoing effects of systemic racism while simultaneously urging Black Americans to embrace personal accountability and conventional family values.

This perspective, coupled with his engaging charm, established him as a significant voice in Black politics and culture. He was Massachusetts co-chair for Reverend Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign and reportedly inspired the character of Dr. Cliff Huxtable on “The Cosby Show.”

Dr. Poussaint consistently denied being the model for Mr. Cosby’s character, but nonetheless, he acted as a crucial advisor. He reviewed nearly every script, pitching suggestions to avoid stereotypes, enhance storylines, and guide writers tackling sensitive topics.

“I don’t rewrite,” Dr. Poussaint explained to The Philadelphia Daily News in 1985. “But I indicate what makes sense, what’s off, what’s too inconsistent with reality.”

Long before Mr. Cosby faced allegations from over 50 women regarding sexual misconduct, he was seen as America’s Dad, a strict yet loving figure to the Huxtable family and to the nation. Much of the guidance Huxtable provided to Black youth reflected Dr. Poussaint’s long-standing messages. (There is no evidence suggesting Dr. Poussaint was aware of the accusations against Mr. Cosby.)

Dr. Poussaint became a sought-after commentator for reporters seeking insights into Black culture. When the sitcom “Family Matters” introduced the nerdy yet intelligent character Steve Urkel, Dr. Poussaint was consulted.

“The fact that he’s a nerd and very bright may be a step forward,” he shared with The New York Times in 1991, “accepting that a Black kid can be bright and precocious and might end up in an Ivy League school.”

He served as a consultant for both “The Cosby Show” (1984-1992) and its spinoff, “A Different World” (1987-1993). He authored the introduction and afterword for Mr. Cosby’s 1986 bestselling book, “Fatherhood”; together, they co-authored “Come On, People: On the Path From Victims to Victors” (2007).

By the time “Come On, People” was released, Dr. Poussaint expressed serious concern for the state of Black men, particularly the youth. His older brother, Kenneth, had faced numerous challenges with incarceration, rehabilitation, and mental health issues, a situation Dr. Poussaint viewed as a blend of personal and societal failures.

Alongside journalist Amy Alexander, he wrote “Lay My Burden Down: Suicide and the Mental Health Crisis Among African-Americans” (2000). In the 2000s, he took several tours across the country with Mr. Cosby, engaging with Black men and families.

“I think a lot of these males kind of have a father hunger and actually grieve that they don’t have a father,” he mentioned to Bob Herbert, a columnist for The Times, in 2007. “And I think later a lot of that turns into anger. ‘Why aren’t you with me? Why don’t you care about me?’”

By then, Dr. Poussaint was addressing a new wave of Black Americans — different from those who learned from “The Cosby Show” — and some critics deemed his messages overly simplistic. He also faced backlash for suggesting that racism could be classified as a mental disorder.

“It’s time for the American Psychiatric Association to designate extreme racism as a mental health problem,” he posited in The Times in 1999. “Otherwise, racists will continue to fall through the cracks of the mental health system, and we can expect more of them to act out their deadly delusions.”

That stance, however, faced criticism for potentially exonerating racists and misrepresenting the systemic nature of racism in American society.

Nevertheless, Dr. Poussaint continued to find support among those who appreciated his nuanced approach in acknowledging racism without permitting it to serve as a justification for what he perceived as nihilism and irresponsibility.

“I always wonder, whenever I talk to Dr. Poussaint, why he isn’t better known,” Mr. Herbert reflected. “He’s one of the smartest individuals in the country on issues of race, class, and justice.”

Alvin Francis Poussaint was born on May 15, 1934, in East Harlem, one of eight siblings of Christopher Poussaint, a printer, and Harriet (Johnston) Poussaint, who managed the household.

Dr. Poussaint characterized himself as a diligent, serious child, contrasting sharply with his brother Kenneth, with whom he shared a room. Kenneth struggled with mental health issues and substance abuse during his adolescence, which led him to commit minor thefts to fund his addiction. He passed away from meningitis in 1975.

This experience, along with a childhood episode of rheumatic fever, motivated Alvin to pursue medicine. He graduated from Columbia University in 1956 and obtained his medical degree from Cornell in 1960, later completing his residency at UCLA, where he also earned a master’s degree in pharmacology in 1964.

While in Los Angeles, Dr. Poussaint became increasingly convinced that racism was triggering a mental health crisis for Black Americans. At the invitation of civil rights leader Bob Moses, he relocated to Jackson, Mississippi, to serve as the Southern field director for the Medical Committee for Human Rights, working to desegregate medical facilities and provide care and training for civil rights activists.

He participated in the 1965 Selma to Montgomery march, carrying a briefcase full of medical supplies, understanding and anticipating that few white individuals along the route would extend help.

In 1973, Dr. Poussaint wed Ann Ashmore in a ceremony presided over by Mr. Jackson. They had a son, Alan, and divorced in 1988. In 1992, he married Dr. Young, a radiology professor at Harvard Medical School, with whom he had a daughter, Alison.

He is survived by his wife, son, daughter, and sister, Dolores Nethersole.

Dr. Poussaint joined the faculty at Tufts University School of Medicine in 1967, moving to Harvard in 1969, where he became the founding director of the school’s Office of Recruitment and Multicultural Affairs. He retired in 2019.

His experiences in the South were difficult; he often faced derogatory treatment from police officers who would call him “boy” and threatened him when he insisted on being addressed as “Dr.”

As he recounted to The Boston Globe in 1996, his involvement with the civil rights movement left him doubtful about whether America could truly vanquish its deeply rooted racism.

“When I was involved in the civil rights movement in the South, I believed, along with many of my colleagues, that we could make significant changes in 10 or 20 years; we were going to rid the country of racism,” Dr. Poussaint stated.

He continued, “However, as time went on, I understood just how ingrained it was in American culture: it was woven into the fabric of the nation’s self-identity, influencing behavior and shaping individuals’ self-worth, often at the expense of Black people and other marginalized groups.”