The rivalry between quantum and classical computers is heating up, highlighted by a recent claim that a quantum annealing processor solved a complex real-world problem in minutes, while a classical supercomputer would take millions of years and consume an immense amount of energy. A differing perspective emerged when another team demonstrated a classical approach solving a subset of the same problem in just over two hours, arguing their method was more accurate. Despite these contrasting results, the D-Wave researchers celebrated a significant milestone in quantum computing, stating their quantum simulations exceeded current classical capabilities in specific cases, particularly infinite-dimensional systems.

The competition between quantum computers and classical computers is heating up.

In a matter of minutes, a unique quantum processor known as a quantum annealing processor reportedly solved a complex real-world problem that could take a classical supercomputer millions of years to complete, researchers claim in a March 12 report in Science. Moreover, the supercomputer, as reported by the team, would require more energy for the entire computation than the entire world consumes in a year. In contrast, another research team asserts they have already discovered a method for a classical supercomputer to tackle a subset of the same issue in just over two hours.

Quantum computers utilize principles of quantum mechanics, potentially providing significant advantages in processing speed and power over the classical computers we use daily. This capability allows quantum computers to address challenges much more rapidly than their classical counterparts.

The latest results, which conflict with one another, echo similar claims made in recent years. The emerging field of quantum computing has progressed alongside efforts to make supercomputers more efficient, creating a closely contested rivalry. While quantum computers have shown the ability to solve genuinely random problems faster than classical computers, they have yet to outperform them for physical challenges relevant to real-world systems.

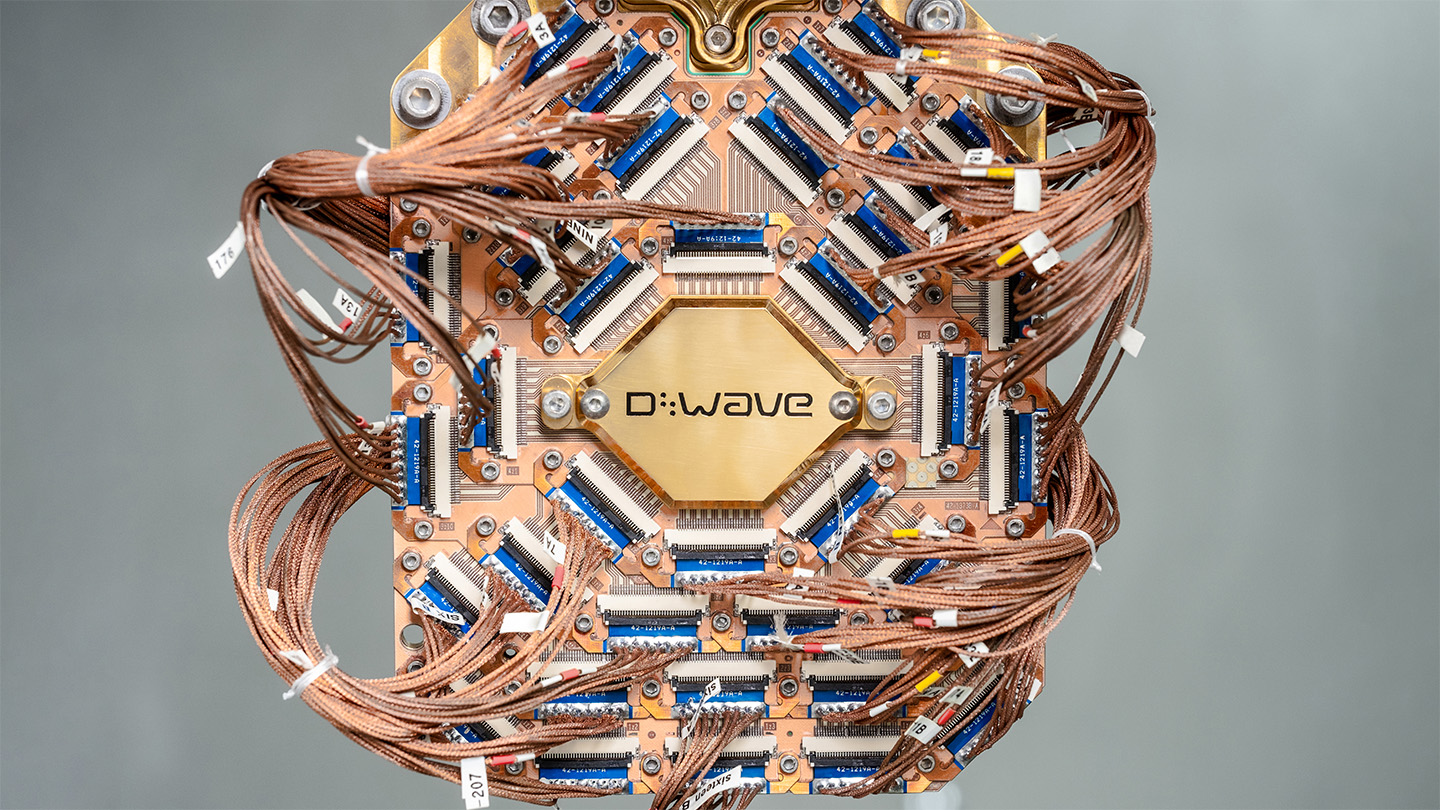

In this recent comparison, a team from D-Wave Quantum Inc. in Burnaby, Canada, employed a quantum computer featuring a quantum annealing processor. These processors differ from other more conventional quantum processors and have demonstrated potential in executing specific tasks. Their design enables them to handle large problems effectively, as their quantum bits (qubits) are interconnected with numerous other qubits rather than just one, as is the case in other quantum processor types. However, they are suitable mostly for particular problem types, such as optimization challenges, and have faced skepticism in the scientific community.

In this latest finding, the D-Wave researchers applied a quantum annealing processor to simulate quantum dynamics utilizing arrays of disorder-magnetized pieces, known as spin glasses. This approach is pertinent to materials science, as comprehending how these systems evolve can aid in formulating new metals.

“This simulation focuses on magnetic materials,” states Mohammad Amin, chief scientist at D-Wave. “Magnetic materials play a crucial role in both industry and daily life,” appearing in devices like cell phones, hard drives, and specialized medical sensors.

The researchers simulated the evolution of such systems in two, three, and infinite dimensions. Following attempts to address the problem through approximations on a supercomputer, they concluded it was unfeasible within a reasonable timeframe.

“This represents a crucial milestone in quantum computing,” asserts Andrew King, a quantum computer scientist at D-Wave. “We have demonstrated quantum supremacy for the first time on a genuine problem of real interest.”

Physicist Daniel Lidar, director of the quantum computing center at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, concurs that the D-Wave team has achieved a significant milestone. “This is very impressive work,” notes Lidar, who did not participate in either study but works with a D-Wave device. “They successfully executed quantum simulations on their hardware that exceed the capabilities of existing classical methods.”

However, the claim does spark controversy. King and his colleagues released a preliminary version of their paper on arXiv.org about a year ago, allowing another group of researchers to scrutinize the findings.

Quantum computer scientist Joseph Tindall from the Flatiron Institute in New York City and his team simulated a portion of the same problem using a classical computer. They developed a technique that rehashed a 40-year-old algorithm called belief propagation, typically employed in artificial intelligence. Their findings, submitted to arXiv.org on March 7 but not yet peer-reviewed, claim to offer more accurate results than the quantum computer’s for certain instances of the two- and three-dimensional systems.

“For the … spin glass problem at hand, our classical method clearly outperforms other reported approaches,” the group states in a draft of their study. “In certain cases, we also achieve errors significantly lower than those observed with the quantum annealing approach used by the D-Wave Advantage2 system.”

The classical simulations focused solely on a subset of the D-Wave results, and the two research groups disagree on whether the classical simulations can replicate all the capabilities of the quantum computer simulations, particularly concerning the three-dimensional system.

Nevertheless, the quantum computer undeniably excelled in the infinite-dimensional system. While not strictly physical, this system is beneficial for enhancing artificial intelligence. Simulating it using classical methods would require a completely different approach than for the two- and three-dimensional systems, Lidar points out. Whether this can actually be achieved is still an open question.