Ancient humans inhabited the Tibetan Plateau, the world’s highest plateau, during the last glacial maximum (26,500 to 19,000 years ago), a period marked by extreme cold and low oxygen levels. Previously deemed uninhabitable, evidence now confirms human presence through the discovery of 427 artefacts, including stone tools and ochre pieces, at a site 3,800 meters above sea level in the Yarlung Tsangpo River valley. Radiocarbon dating indicates three occupation phases between 29,200 and 23,100 years ago, coinciding with the glacial maximum. These findings suggest the valley provided essential resources, supporting the theory that it acted as a refuge for early Tibetans.

Early humans thrived on the Tibetan Plateau—the highest plateau on the planet—during the harshest period of the last 2.5 million years, highlighting their extraordinary resilience and adaptability.

The last glacial maximum, spanning from 26,500 to 19,000 years ago, represented the most brutal phase of the Late Pleistocene ice age. Massive ice sheets and polar ice caps blanketed vast areas of the Earth during this time, with global temperatures averaging about 4 to 5 degrees Celsius lower than those of today, as reported by the New Scientist .

“The Tibetan Plateau was once considered uninhabitable during the last glacial maximum,” states Wenli Li from the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. “Survival was extremely challenging due to the extreme cold, sparse vegetation, and low oxygen levels at high altitudes.”

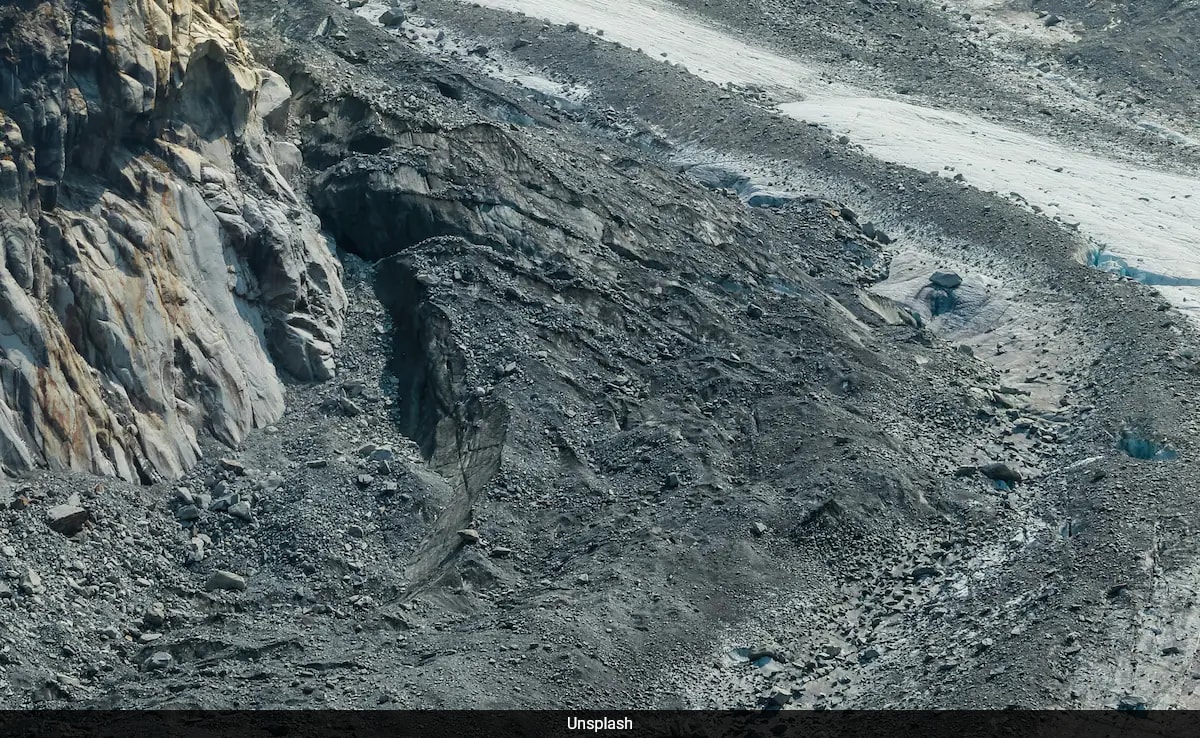

While previous evidence indicated human habitation on the plateau before and after the last glacial maximum, no evidence of occupation during this time-frame had been discovered—until now. In 2019, Li and her research team found a site located 3,800 meters above sea level in the Yarlung Tsangpo River valley on the southern Tibetan Plateau, which yielded numerous artefacts pointing to human presence.

The researchers uncovered 427 artefacts, including stone tools and the first pieces of ochre—the red rock used in ancient art—ever found in Tibet.

Radiocarbon analysis of ancient bones and charcoal from the site revealed three separate periods of human activity between 29,200 and 23,100 years ago. Two of these periods, around 25,000 and 23,000 years ago, align with the last glacial maximum.

“No archaeological site had been dated to this epoch before,” remarks Feng He from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who was not part of the study. “This finding strengthens the notion that early humans were extremely resilient and adapted well to severe conditions.”

To gain insights into the environment during these periods of occupation, researchers examined nearby stalagmites and lake cores, which offer climate data through their chemical properties. Their results indicate that the river valley may have had more moisture than previously thought for the arid ice age in Tibet, allowing for the survival of cold-tolerant plants and herbivores.

“The valley likely supplied essential resources—water, vegetation, and game necessary for survival,” Li explains.

The stone tools found at this site bear similarities to those from older sites further north within the plateau, suggesting that as climate conditions became colder and drier, populations migrated into the river valley, according to Li.

Earlier studies had suggested that river valleys in the southern Tibetan Plateau could have acted as refuges for residents fleeing the increasingly severe cold of the last glacial maximum, He adds. “It’s gratifying to see this discovery supports that theory.”

Moving forward, Li and her team aim to delve deeper into how climatic changes during the last glacial maximum influenced human migration and habitation at the site, which they have named Pengbuwuqing after a nearby hill.