Frank G. Wisner II, an influential American diplomat and foreign affairs expert, passed away at 86 due to lung cancer complications. Over a distinguished career, he served as ambassador to Zambia, Egypt, the Philippines, and India, navigating complex Cold War dynamics and playing significant roles in various diplomatic initiatives. Wisner was known for his gregarious nature and personal style of diplomacy, exemplified during his ambassadorship in Cairo, where he engaged in important back-channel negotiations. Following his retirement in 1997, he remained active in private sector advisory roles and expressed concerns about U.S. foreign policy mistakes in Iraq and Afghanistan.

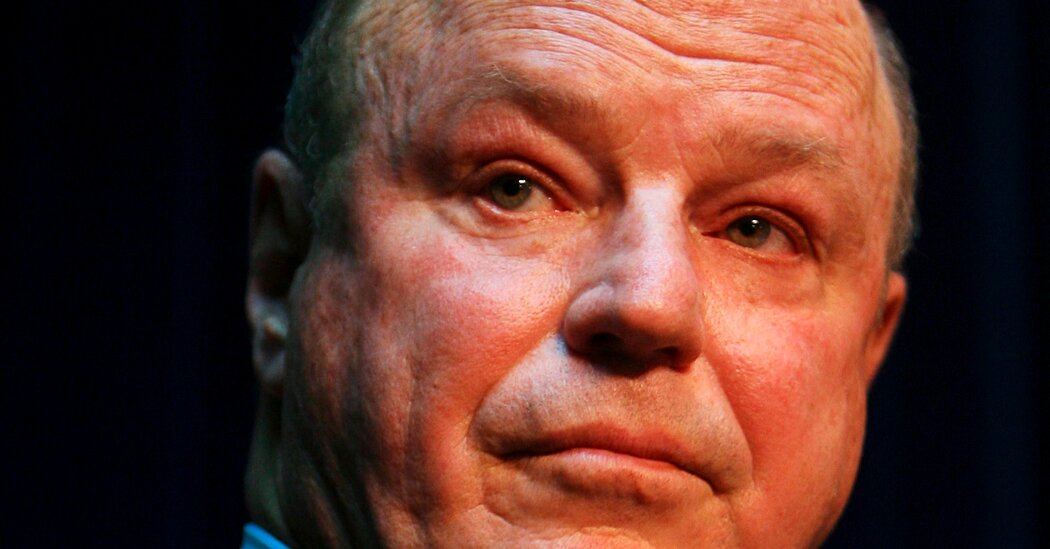

Frank G. Wisner II, a seasoned American diplomat and insider in Washington’s foreign affairs, who enjoyed the prestige of ambassadorial duties just as much as the subtle art of back-channel persuasion, passed away on Monday at his home in Mill Neck, N.Y., Long Island. He was 86 years old.

His son, David, confirmed that the cause of death was complications arising from lung cancer.

Throughout his long career among the elite of policy-making, Mr. Wisner led embassies in nations such as Zambia, Egypt, the Philippines, and India, served in significant roles under both Republican and Democratic administrations, and played a part in transformative initiatives across areas ranging from southern Africa to the Balkans.

He gained prominence during the Cold War era, a time when the emerging world of newly-independent states became a battleground for influence between Washington and Moscow, alongside their respective proxies.

Known for his gregarious nature, Mr. Wisner infused his own approach into promoting America’s agenda. For example, while serving as ambassador in Cairo from 1986 to 1991, he invited a journalist to accompany him on an evening of diplomacy, traversing the city in an armored Mercedes-Benz with a security vehicle in tow, attending a series of formal receptions.

The guest list at his dinner gatherings read like a roster of the elite, and as the envoy for Egypt’s key superpower ally, some of his conversants treated him like a charming viceroy.

On one occasion, Mr. Wisner utilized a friend’s apartment in Cairo for discreet discussions with exiled members of the Soviet-supported faction of Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress, a rare engagement at that time.

As the American ambassador in Egypt during Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, which led to a large-scale counter-invasion of Iraq by U.S. forces, Mr. Wisner felt the ripple of anxiety among Western diplomats throughout the Arab nations. However, while some diplomatic missions were either evacuating their personnel or shutting their operations, Mr. Wisner reflected in a 1998 interview, “we stayed put.” His confidence in the Egyptian government’s capability to maintain order on the streets, along with faith in their diplomatic ties, guided his decision.

“We understood the Egyptians well,” he commented. “They understood us just as well. We were aligned.”

In Manila, where he served as ambassador to help stabilize the politically volatile administration of Corazon Aquino, his office was within the historical suite of the American governor-general.

“Cigar in hand, he delighted in taking guests out to the expansive veranda with views of the bay, recounting the history of American relations with the Philippines, dating back to the era of the Spanish-American War,” reported The New York Times.

However, well after retiring from public service in 1997 and beginning a prosperous career as a senior adviser for private firms, Mr. Wisner’s last act of public diplomacy during the 2011 Arab Spring faced difficulties, as he found himself at odds with the Obama administration and marginalized from mainstream U.S. policymaking.

Amidst massive protests in Cairo’s Tahrir Square demanding the removal of pro-American President Hosni Mubarak, President Barack Obama sent Mr. Wisner to convey a message to his Egyptian counterpart, someone he had come to know well during his tenure there.

President Obama aimed for Mr. Mubarak to begin transferring power immediately. Unfortunately, after their initial meeting, Mr. Mubarak hesitated, asserting that he would state he would not seek re-election in the upcoming months but desired to stay in office until then. Mr. Wisner, who also conferred with Egyptian Vice President Omar Suleiman during this mission, was instructed to return to the U.S.

Shortly thereafter, addressing a large security conference in Munich via video link, Mr. Wisner emphasized the importance of Mr. Mubarak remaining in place to oversee the transition.

These comments were quickly rebuffed by both the State Department and the White House, asserting that Mr. Wisner was expressing personal opinions that did not align with the official stance.

This marked a rare and awkward public reprimand.

News reports suggested that President Obama was angered by Mr. Wisner’s unanticipated statement, which seemed to indicate a cautious approach towards regional stability from a foreign policy establishment that prioritized preserving Egypt’s 1979 peace agreement with Israel—a key component of American strategy in the area—over backing the revolutionary calls from citizens seeking Mr. Mubarak’s resignation.

Ultimately, Mr. Mubarak, who passed away in 2020 at 91, was compelled to resign shortly thereafter amidst escalating protests against him.

In later years, during an online conversation hosted by the Council on Foreign Relations, Mr. Wisner appeared to stand by his views.

“During the Obama administration, I was tasked with conveying a message to Mubarak regarding his departure from office,” he stated. “I followed instructions.” However, he added, “the policy shifted, which was disheartening for me.” He believed that the United States should position itself as “a force for problem-solving,” rather than merely leading protests.

He further noted, “It undermined our standing in the region. And we learned that we had no control over the future of the Egyptian revolution.”

Frank George Wisner II was born on July 2, 1938, in Manhattan to Frank Gardiner Wisner and Mary Knowles Wisner. His father, an intelligence operator during World War II, later joined the Central Intelligence Agency and was credited with orchestrating coups in Guatemala and Iran before dying by suicide in 1965.

The younger Mr. Wisner had two brothers, Graham and Ellis, and a sister, Elizabeth Gardiner Wisner, who passed away in 2020. Graham died in January.

In his early years, Mr. Wisner spent time at the prestigious Rugby School in England before proceeding to Princeton University. He began his career with the State Department in 1961, receiving initial assignments in newly-independent Algeria, war-torn South Vietnam, Tunisia, and Bangladesh.

In 1969, he wed Genevieve de Virel, a member of a prominent French family, who died in 1974, leaving behind a daughter, Sabrina.

In 1976, he married Christine de Ganay, who was also from an aristocratic French lineage and the ex-wife of Pal Sarkozy, father of former President Nicolas Sarkozy of France. Their son is David Wisner, and Christine had two children from her previous marriage, Olivier and Caroline Sarkozy. The couple later divorced, and Mr. Wisner married Judy C. Cormier, an interior designer, in 2015.

He is survived by his wife and children, as well as his brother Ellis and twelve grandchildren.

In interviews following his retirement from the State Department, Mr. Wisner frequently referenced his involvement during the Nixon administration, working with Henry A. Kissinger as the White House sought to negotiate a conclusion to the guerrilla warfare in Zimbabwe, historically known as Rhodesia, throughout the 1970s.

During that period, Moscow and Washington were competing for influence across a range of tumultuous African nations, including Mozambique, Angola, Namibia, and eventually South Africa. In Angola, this struggle entailed the involvement of Cuban and South African forces backing opposing liberation movements.

While serving as ambassador to Zambia from 1979 to 1982, one of his objectives was to restore a strong relationship with President Kenneth D. Kaunda following the revelation of undercover CIA operations in 1981.

During that time, Lusaka, the seemingly peaceful Zambian capital, was bustling with representatives from various liberation movements backed by the Soviet Union and China, alongside Western intelligence operatives aiming to monitor and undermine them. Zambia played a crucial role in the Frontline States, historically providing essential support and diplomatic cover for liberation movements across the region.

“There were certainly some tense moments” during his efforts to repair the damage, Mr. Wisner recalled in a 1998 Library of Congress interview.

In fact, Mr. Wisner was a key figure in the Reagan administration’s “constructive engagement” policy, led by Chester A. Crocker, the former assistant secretary of state for African affairs. This strategy rested on the belief that the apartheid regime of South Africa could be persuaded to ease its hold on power instead of engaging in destructive battles against Black movements demanding majority rule.

In his 1992 publication “High Noon in Southern Africa,” which chronicles American diplomacy in the region, Mr. Crocker referred to Mr. Wisner as “the dean of Southern Africa specialists,” noting his unmatched breadth of foreign affairs experience within the government and highlighting his “refined, understated demeanor and personable warmth.”

Over the course of his career, Mr. Wisner shifted between international assignments and senior positions in Washington, including roles at the State Department and the Pentagon.

Even after his retirement from diplomacy in 1997, he continued to blend roles in the private sector with diplomatic missions. In 2005, during the George W. Bush administration, he was appointed special representative in negotiations that led to the disputed independence of Kosovo in 2008.

Following his 1997 retirement, he pursued a second career in business, taking on the role of vice chairman at the insurance giant A.I.G. and working as a consultant in international affairs for Squire Patton Boggs, a legal and lobbying firm in Washington.

In his later years, Mr. Wisner expressed concern regarding America’s global engagement, starting with the Vietnam War in the 1960s and continuing through the protracted conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“We seem resistant to learning from our past mistakes, leading to tragic excesses in Iraq and now Afghanistan,” Mr. Wisner remarked during a June 2021 discussion with the Council of Foreign Relations, shortly before the chaotic U.S. withdrawal from Kabul.

“I hope this chapter of American history, stretching from the late 1960s to the present, will find its way into the collective American consciousness,” he added, “and we will exercise caution in how we wield American power.”